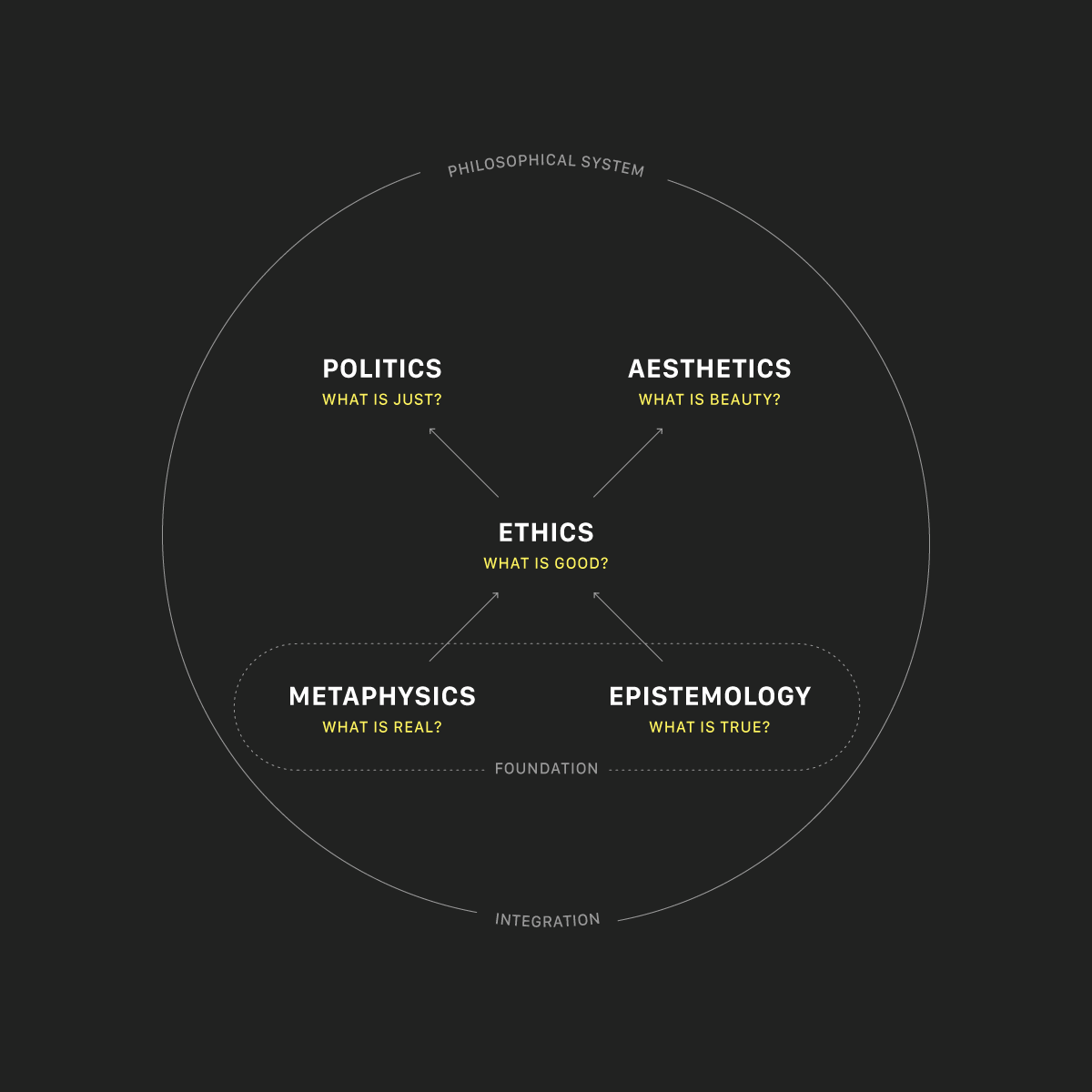

The purpose of this post is to explain the ontology of social facts to create a foundation for future posts. Ontology is a fancy word that refers to the nature of existence. In other words, I want to explain how social facts come into existence. John Searle is perhaps the most influential living philosopher on the subject of social ontology. John Searle's philosophical project is to try to explain how we get meaningful social facts like the existence of money, elections, marriages, touchdowns, cocktail parties etc. Searle frames his work with the following question:

“"How, if at all, can we reconcile a certain conception of the world as described by physics, chemistry, and the other basic sciences with what we know, or think we know, about ourselves as human beings? How is it possible in a universe consisting entirely of physical particles in fields of force that there can be such things as consciousness, intentionality, free will, language, society, ethics, aesthetics, and political obligations? ... This is the single overriding question in contemporary philosophy."

The following provides the conceptual apparatus for answering such a question:

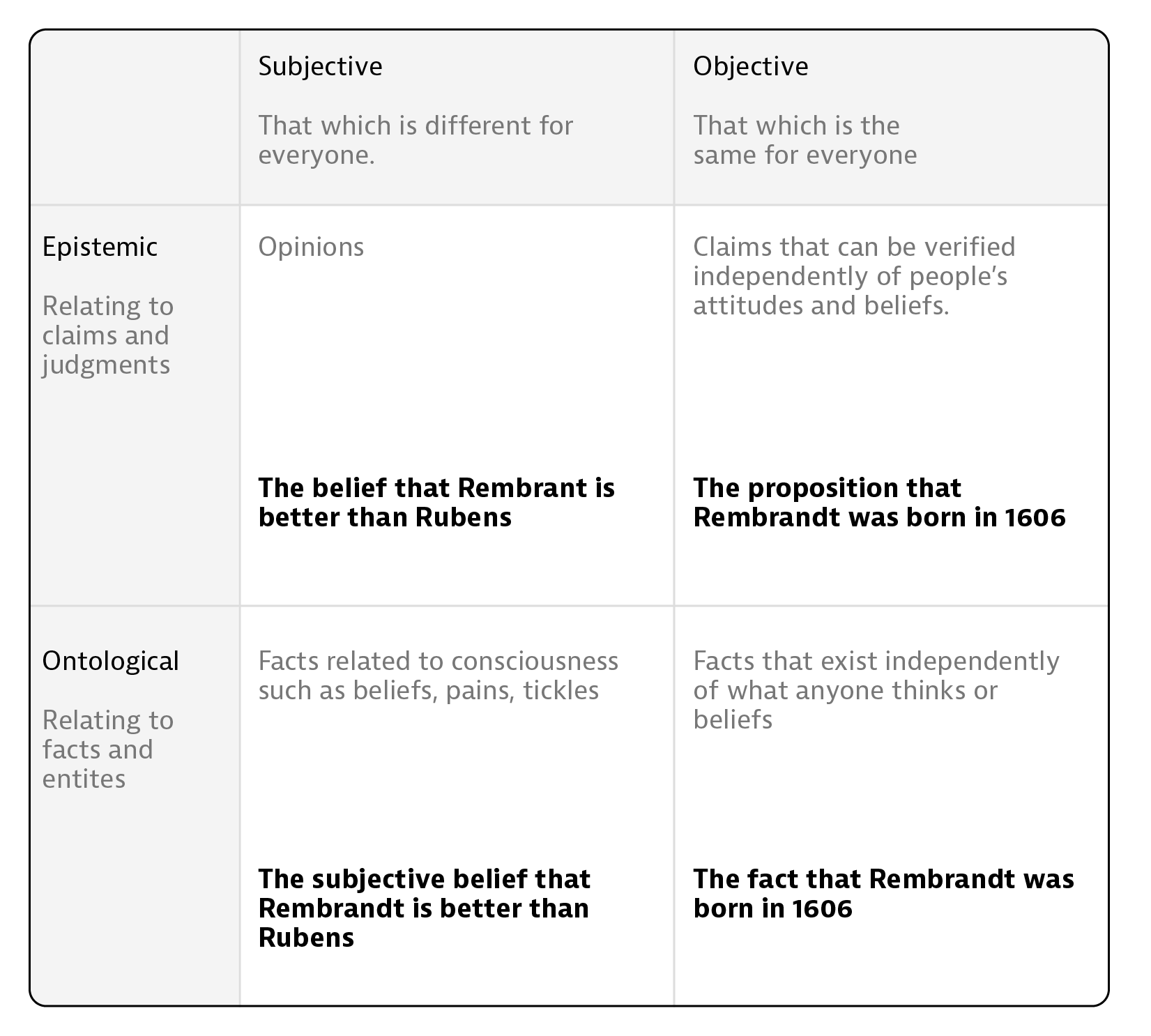

Mind-independent and mind-dependent facts

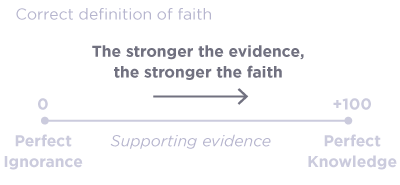

The first conceptual tool necessary to solve the puzzle is the distinction between Mind-Independent facts and Mind-Dependent facts. Mind-independent facts are facts that exist even if all human beings suddenly vanished. These facts include the existence of particles and forces, mountains and rivers, space and time. Mind-Dependent facts on the other hand exist only because they are created by the beliefs of conscious beings. If we go, they go. Mind-Dependent facts include such things as money, elections, marriages, touchdowns, cocktail parties, religious sacraments, lawyers, good and evil etc. So we are concerned primarily with this class of fact. In previous posts, I have called these observer-independent/dependent facts. Sometimes I refer to mind-independent facts as Brute Facts.

mind-indpendent-dependent

Collective recognition

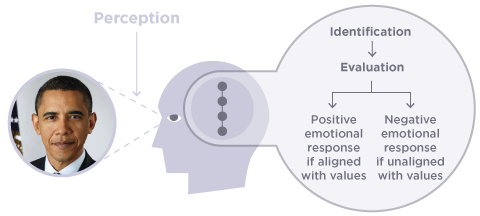

Social facts require human cooperation. Mind-Dependent facts are only facts if everyone collectively recognizes and accepts them as facts. For examples, Barack Obama is president of the united states only because he is collectively recognized as being the president. If people stopped recognizing him as such, then he would cease to be president. Collective recognition does not mean that everyone explicitly supports a given fact, but at a minimum they have to implicitly accept it or go along with it.

Assignment of function

All functions are Mind-Dependent. Functions only exist relative from conscious beings who represent objects as having a certain function.

Both human beings and higher animals can impose functions on objects. For example, a rock by itself doesn't have any function, but in the hands of a monkey it can serve the function of a mallet or hammer. Similarly, a screwdriver has no innate function. It only has the function of a screwdriver because humans assign it that function. In both of these cases, the function is matched with some physical property or shape of the object.

Status functions

Humans are unique in that they have the ability to assign functions to objects or people regardless of the physical structure of that object or person. So for example, we can assign the status of money to a piece of paper, or the status of chairman to an individual. Unlike the screwdriver whose function matches its shape, there is really nothing about the piece of paper that makes it money. Likewise, there is nothing intrinsic about Barack Obama that makes him president either. He is president because everyone collectively recognizes his status. The collective assignment of function to objects results in a Status Function. Status functions cannot exist without collective recognition. Status functions are pervasive. We are basically locked into an invisible system of status functions. How do status functions work in the real world anyhow?

Constitutive rules

There are 2 types of rules—regulative rules and constitutive rules. Regulative rules regulate preexisting forms of behavior. For example, the rule to drive on the right side of the road is a regulative rule. On the other hand, constitutive rules don't regulate antecedently existing forms of behavior, they create the very possibility of the behavior that they regulate. Take the example of Chess, the rules of chess create the very possibility for the existence of chess. Without the constitutive rule, there would be no chess moves to regulate at all. Regulative rules regulate activities that could exist independently of rules. But, constitutive rules regulate activities that are dependent on the rules for their existence. Status functions exist only relative to a system of constitutive rules.

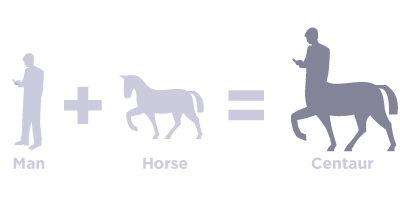

The constitutive rules of status functions have the structure "X counts as Y in context C". For example, this piece of paper(X) counts as $1(Y) in the United States(context C). Barack Obama(X) counts as the president(Y) of the United States(C). Such and such a move(X) counts as a legal knight move(Y) in the game of chess(C). The fascinating feature of this structure is that it can iterate upward indefinitely where the "Y" term from a lower level can constitute an "X" term at a higher level. For example:

Such and such a noise(X1) counts as a sentence(Y1) in English. Such and such an english sentence(Y1=X2) can count as making a promise(Y2) Uttering such and such a promise(Y2=X3) counts as undertaking a marriage contract(Y3).

This iterative feature can be illustrated with the lowest level at the bottom as such:

iteration

Summary so far

So far I have explained that social facts are collectively recognized status functions. These status functions are created by the constitutive rule "X counts as Y in context C". This rule can iteratate upward indefinitely. Another feature of status functions is that they almost never exist alone. They always exist as part of a much larger systems of constitutive rules. Status functions ultimately bottom out in brute facts that are Mind-Independent. For example, is assigned to some physical brute fact such as a piece of gold, or a piece of paper or a magnetic trace on a computer disc.

Exceptions

There are some exceptions to the constitutive rule "X counts as Y". Sometimes we can just create a "Y". One example is the corporation. To create a corporation we just say we are creating a corporation. There is no brute fact "X" that is the corporation. It isn't the building of the business or the businessmen. This ingenious social fact allows people to make money while being protected from losses.

The role of language

Language is essential to the existence of status functions. You can imagine a tribe that a had language but didn't have money, or private property, or governments, but you can't imagine having money and governments without language.

Language is a system of constitutive rules and is necessary for the creation of status functions. As I wrote in a previous post, there are 5 and only 5 things you can do with language. Here, I just want to talk about one of the things one can do with language called "Declarations". Declarations are speech acts that change reality by representing reality as being so changed. A rough test to see if something is a declaration is if you can add the word “hereby” in front of it as in “I hereby declare war.” Examples of declarations include “this meeting is adjourned”, “I now pronounce you husband and wife” and,”This note is legal tender for all debts public and private”. Status functions are language-dependent. Social facts exist because we use language to declare that they exist.

Status functions have power!

Status functions are the glue that hold society together because they have power. According to John Searle:

Without exception, the status functions carry what I call “deontic powers.” That is, they carry rights, duties, obligations, requirements, permissions, authorizations, entitlements, and so on. I introduce the expression “deontic powers” to cover all of these, both the positive deontic powers (e.g., when I have a right) and the negative deontic powers (e.g., when I have an obligation),

The status function of money entitles me to buy goods. The status function of President of the United States authorizes the president to give certain orders. The president is also put under an obligation to uphold the constitution. Some deontic powers are conditional. For instance, in some states a voter can vote for a political candidate only upon the condition that the voter is registered for the party of that candidate.

Desire-independent reasons for action

Status functions can lock into human rationality by providing desire-independent reasons to acting in a certain way. These reasons are created by the deontic powers of status functions. For example, the president has reasons for upholding the constitution regardless of whether he wants to or not because he has the status function of being the president. Employees have an obligation to come into work even when he/she doesn't feel like it. The status function of husband provides the man reasons to act differently than his initial inclinations—to be faithful, and to protect his family and so forth.

Summary

To summarize, the ontology of social facts come from the collective recognition of status functions which are created through constitutive rules. These constitutive rules usually have the logical form "X counts as Y in context C" and are created by speech acts called "Declarations". Since I have learned about status functions, reading the news has been fascinating because I can see the world in terms of status functions. In future posts I plan to apply this way of analyzing social ontology to the subjects of human rights and religious institutions.