There is much confusion surrounding the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity. Basically defined, objectivity refers to that which is the same for everyone while subjectivity refers to that which is different for everyone. In the book, Making the Social World: The Structure of Human Civilization, the famous philosopher John Searle poses a fascinating question related to objectivity, subjectivity, and social reality:

How is it possible that we can have factual objective knowledge of a reality that is created by subjective opinions? One of the reasons I find that questions so fascinating is that it is part of a much larger question: How can we give an account of ourselves, with our peculiar human traits - as mindful, rational, speech-act performing, free-will having, social, political human beings - in a world that we know independently consist of mindless, meaningless, physical particles? How can we account for our social and mental existence in a realm of brute physical facts?

One part of the answer is giving a better understanding of the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity. One of Searle’s favorite examples is money which provides a concrete example to solve the paradox:

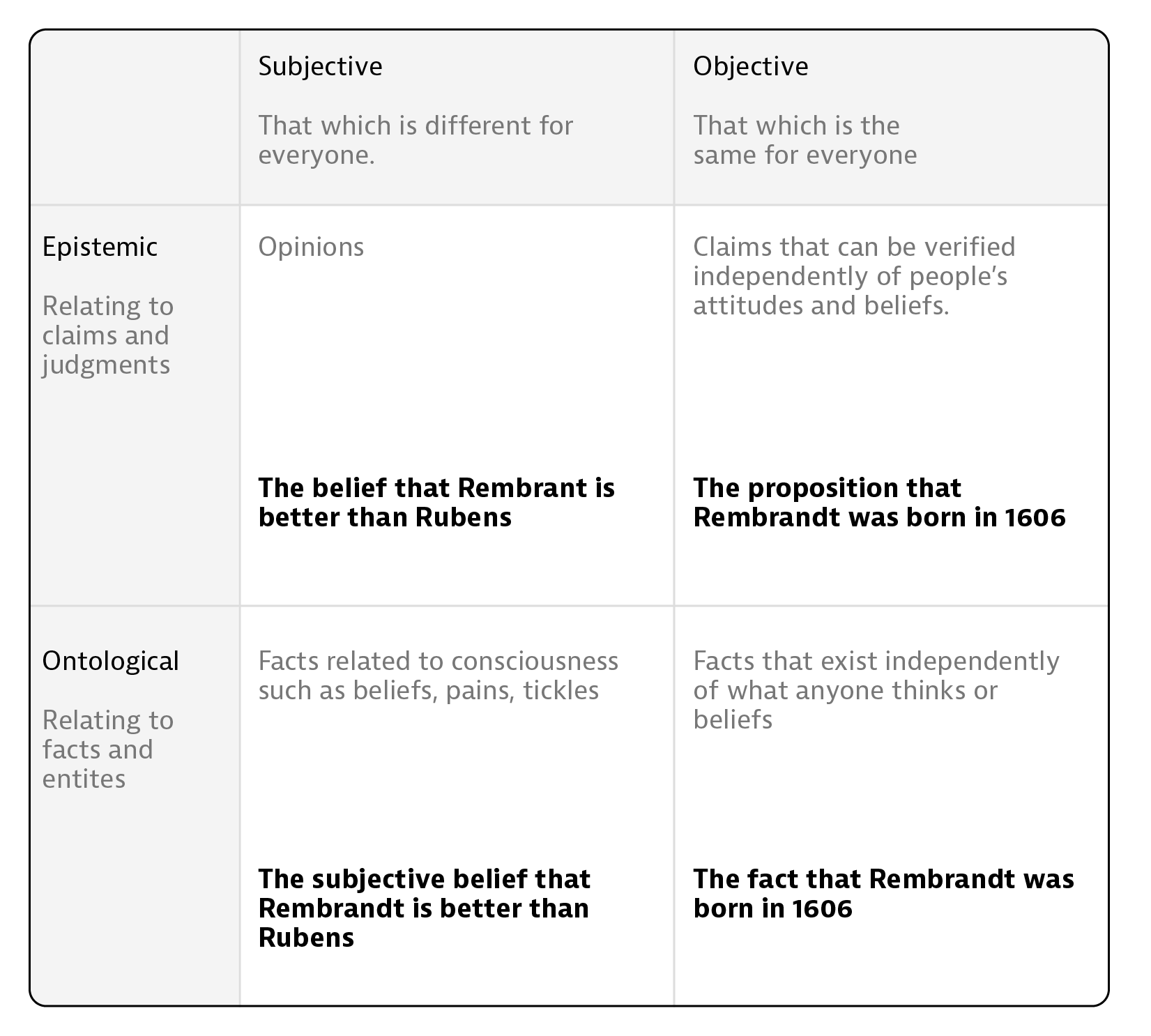

One reason why the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity are so misunderstood is that there is ambiguity between different senses of each of these terms. There is an epistemic sense and there is an ontological sense for each term. “Epistemic” simply means relating to claims or knowledge more generally. Epistemology is the study of knowledge. “Ontological” means pertaining to entities. Ontology is the study of existence. The question of social facts seems paradoxical because the objective/subjective distinction doesn't account for ontological and epistemic dimensions. Here is a diagram that spells out these distinctions:

In the first row of the above diagram, there are epistemically subjective beliefs. We call these opinions because there is no fact behind those beliefs that make it the same for everyone. Some people like Rembrandt better, some like Rubens better. On the left side, we have the proposition that Rembrandt was born in 1606. This is an epistemically objective claim because, unlike epistemically subjective beliefs, there is a fact of the matter that makes epistemically objective propositions true for everyone. When an epistemically objective proposition accurately reflects reality, we say that it is “true”. This is the correspondence theory of truth.

In the second row of the diagram, there is the ontological dimension. On the bottom right, we have facts or entities that exist independently of what anyone thinks or beliefs. These include mountains, molecules, tectonic plates, events, etc. The fact that Rembrandt was born in 1606 is an objective event that happened regardless of whether people believe such a fact. The bottom left quadrant is the most interesting. Here we have ontologically subjective entities such as consciousness itself which include our beliefs, emotions, intentions, pains, tickles, etc.

Going back to our example of money, the above distinctions clarify that the proposition that “certain pieces of paper are money” is an epistemically objective claim. But that fact that it is money comes from our ontologically subjective beliefs.

This is not the whole story of money of course, but it does dissolve the paradox of how you can get objectivity from subjectivity. A more complete account of how things like money come from our subjective beliefs would include an explanation of the conditions that are necessary to create ontologically objective facts. These conditions include language, collective intentionality, and status functions to name a few. The existence of language reveals certain features of consciousness such as collective intentionality. Collective intentionality roughly refers to the collective agreement. Status functions are the assignments we make where we assign a purpose to objects and events. In the case of money, we assign certain pieces of paper the function of money and it works because of our collective recognition of this fact. For a more complete explanation, please see my post on social ontology.

The above distinctions are not only useful in understanding social facts such as money, marriage, political appointments, and cocktail parties, but they are useful in dispelling some common misconceptions about science. For example, some people think that because science is “objective” and consciousness is “subjective” that there cannot be a science of consciousness. But this is making the same fallacy of ambiguity that was mentioned earlier. There can indeed be an epistemically objective science about a domain that is ontologically subjective—such as consciousness for example.

There are other misunderstandings about objectivity, such as the belief that objectivity is an illusion because people subjectivity experience the world in different ways. This post provides a foundation to address this error which I plan on address in future posts.