Every fourth friday, I meet with a philosophy group. In our August philosophy discussion, we discussed the essay Individualism: True and False by the social theorist and economist Friedrich Hayek. According to Hayek, there are two opposing ideas about how to understand individuals and the society in which they live. Hayek calls these ideas true individualism and false individualism. These ideas permeate all social and political thought. They apply to beliefs about reason and knowledge, economics, justice, equality, power, tradition, marriage and family, and government. In this post, I will briefly introduce the concepts of true and false individualism and discuss how they relate to ideas about reason and knowledge.

True Individualism and False individualism

True individualism is a social theory that says that individuals cannot be properly understood without understanding the social processes that surround him. As people make individual decisions they contribute to a social order that is not the result of human design. According to Hayek, “if left free, men will often achieve more than individual human reason could design or foresee.” (individualism: True and False pg 11) Hayek associates true individualism with Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, Alexis de Tocqueville, Lord Acton, and John Locke.

False individualism on the other hand asserts that individuals are best understood as existing independently of social processes. And, it seeks to understand society as existing independently of the individuals that compose that society. False individualism assumes that reason "is always fully and equally available to all humans and that everything which man achieves is the direct result of, and therefore subject to, the control of individual reason.” False individualism seeks to free individuals from social constraints in order to promote liberated self-expression. This view has been expressed by John Stuart Mill, Jeremy Bentham, René Descartes, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and, William Godwin.

Reason and Knowledge

According to true individualism, any individual's own knowledge alone is grossly inadequate for social decision making. Knowledge comes primarily from experience which is “transmitted socially in largely inarticulate forms from prices which indicate costs, scarcities, and preferences, to traditions which evolve from the day to day experiences of millions in each generation, winnowing out in Darwinian competition what works from what does not work.” (Conflict of Visions pg 36)

In another work, Hayek wrote that, “man has certainly more often learnt to do the right thing without comprehending why it was the right thing, and he still is better served by custom than understanding.” There is thus, “more ‘intelligence’ incorporated in rules of conduct than in man’s thoughts about his surroundings.” (Law, Legislation, and Liberty pg 157)

In his essay on individualism Hayek argues that since man’s reason is inadequate to intelligently design society, individuals are justified in following, and ought to follow, social conventions that have evolved over time.

...the individual, in participating in the social processes, must be ready and willing to adjust himself to changes and to submit to conventions which are not the result of intelligent design, whose justification in the particular instance may not be recognizable, and which to him will often appear unintelligible and irrational.

Thus according to true individualism, knowledge for how to act in social contexts comes from mostly from experience. It is systemic and dispersed in the many, and is expressed through social norms and customs.

False individualism rejects these ideas in favor of what Hayek calls “Rationalism” which accepts only what can “justify” itself to reason and evidence. One proponent of rationalism—the philosopher William Godwin—expressed this view when he said that “Reason is the proper instrument, and the sufficient instrument for regulating the actions of mankind.” Traditions and social norms are looked upon with skepticism and disdain unless they are validated via specifically articulated rationality. This is because knowledge is viewed as, “conscious, explicit knowledge of individuals, the knowledge which enables us to state that this or that is so-and-so.”

Implicit in Hayek’s view of rationalism is that it can lead to both socialism and extreme forms of libertarianism. Rationalism can lead to socialism because according to Godwin, “persons with narrow views and observation,” readily accept whatever happens to prevail in their society. (Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Vol II, pg 206) It is only the “cultivated minds” who can deliberately see past the social norms and traditions of the masses and deliberately design a society that will benefit all. Rationalism thus sees knowledge and reason as concentrated in the few who see themselves as surrogate decision-makers on behalf of the masses. This is why Hayek believes that rationalism often leads “directly to socialism” which assumes that society can only improve if it is deliberately designed by the wisest most cultivated minds. Taken to another extreme, rationalism can also lead to forms of libertarianism which seeks to reduce all social interactions to deliberate contract making between individuals as if they could deliberately design their lives from scratch apart from society or government.

According to Thomas Sowell who wrote extensively about Hayek, “Rationalism at the individual level is a plea for more personal autonomy from cultural norms, at the social level it is often a claim—or arrogation—of power to stifle the autonomy of others,” on the basis of assumed superior wisdom and articulated rationality. (Knowledge and Decisions pg 103)

Summary

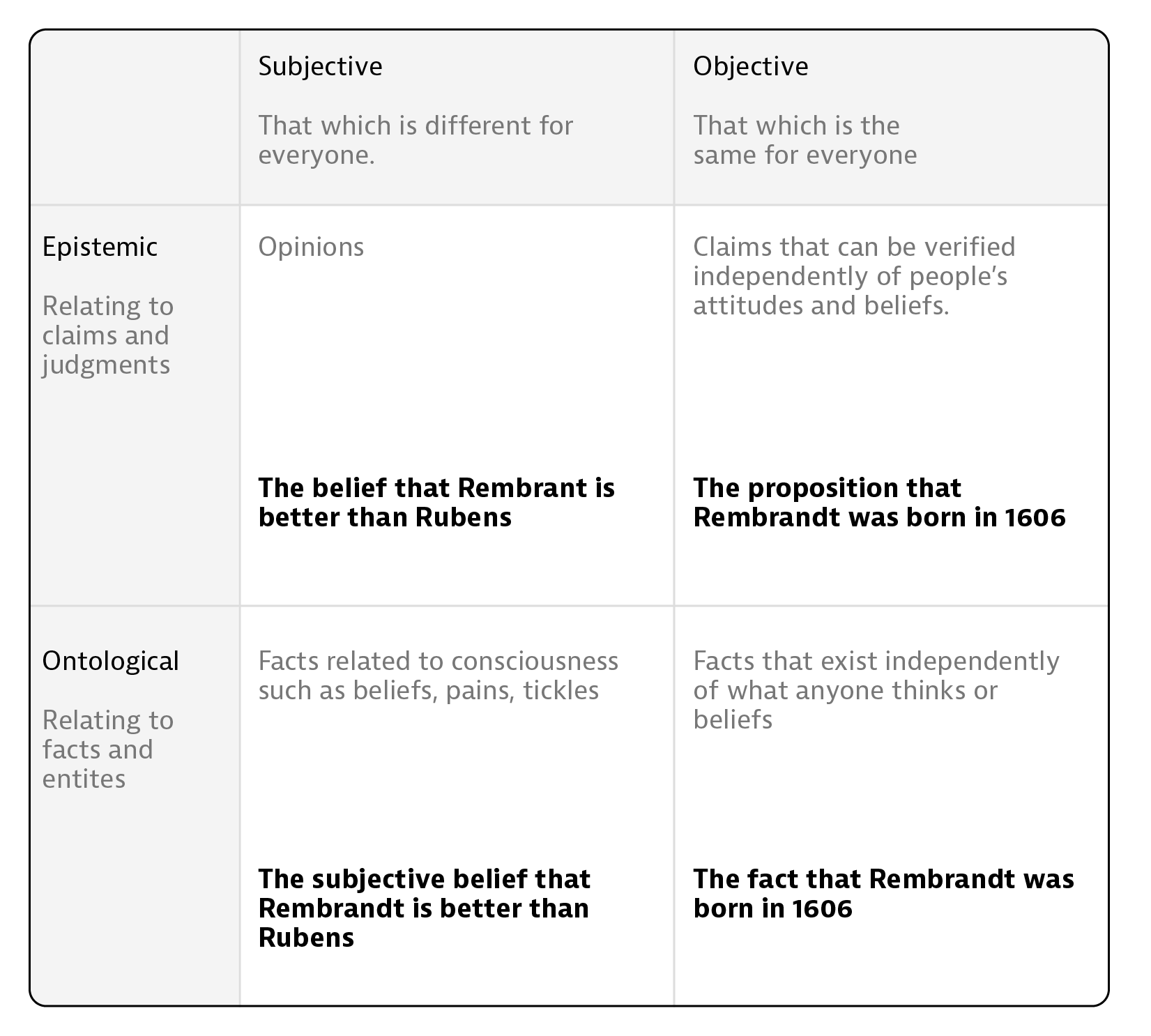

Another way to understand true and false individualism with respect to knowledge and reason is to contrast how each side answers the questions, “what is the locus of discretion?” and, “what is the mode of discretion?” as shown in the graphic below:

According to true individualism, individuals should be left free to make their own decisions within a framework of systemic rationality. Systemic rationality refers to the experience of the many as expressed in social norms, customs, traditions, and even price signals within an economy. According to false individualism, individuals should be free from the constraints of social norms and traditions. They can only be free if they are liberated by experts who exempt themselves from social norms and make social decisions on behalf of “society”. False individualism thus assumes that man can comprehend society enough to design it.

Friedrich Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order

Thomas Sowell, Conflict of Visions

Friedrich Hayek, Law, Legislation, and Liberty

William Godwin, Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, Vol II

Thomas Sowell, Knowledge and Decisions

Notes:

Compare to Conservative Rationalism vs. Enlightenment Rationalism